Excerpt:

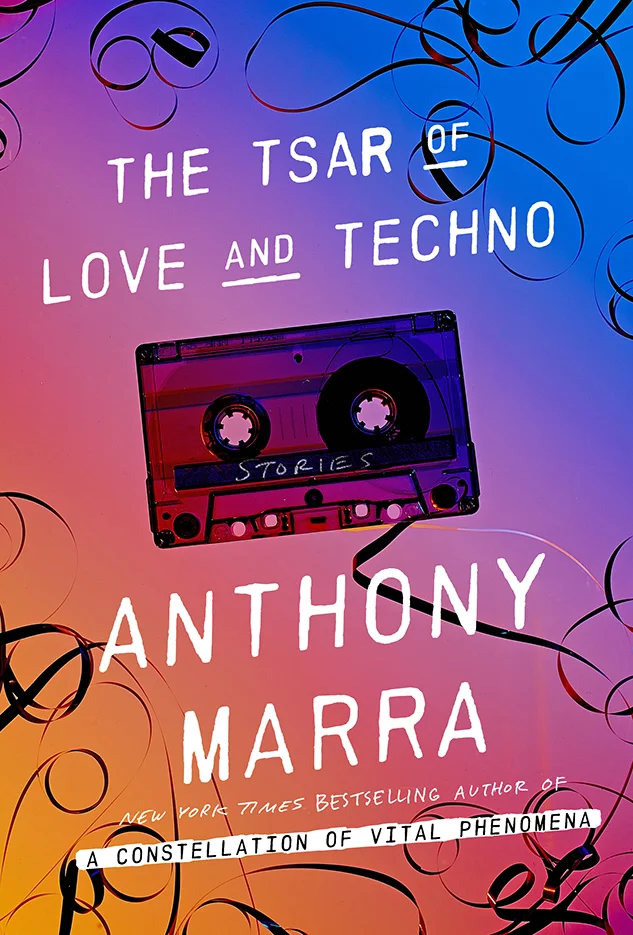

The Tsar of Love and Techno

by Anthony Marra

(available now; Reprinted from the book The Tsar of Love and Techno by Anthony Marra. Copyright © 2015 by Anthony Marra. Published in the United States by Hogarth, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.)

From the New York Times bestselling author of A Constellation of Vital Phenomena—dazzling, poignant, and lyrical interwoven stories about family, sacrifice, the legacy of war, and the redemptive power of art.

This stunning, exquisitely written collection introduces a cast of remarkable characters whose lives intersect in ways both life-affirming and heartbreaking. A 1930s Soviet censor painstakingly corrects offending photographs, deep underneath Leningrad, bewitched by the image of a disgraced prima ballerina. A chorus of women recount their stories and those of their grandmothers, former gulag prisoners who settled their Siberian mining town. Two pairs of brothers share a fierce, protective love. Young men across the former USSR face violence at home and in the military. And great sacrifices are made in the name of an oil landscape unremarkable except for the almost incomprehensibly peaceful past it depicts. In stunning prose, with rich character portraits and a sense of history reverberating into the present, The Tsar of Love and Techno is a captivating work from one of our greatest new talents

“[E]xtraordinary… Each story is a gem in itself. But the book is greater than its parts, an almost unbearably moving exploration of the importance of love, the pull of family, the uses and misuses of history, and the need to reclaim the past by understanding who you really are and what really happened…He starts this miracle of a book by showing us how a system can erase the past, the truth, even its citizens. He ends by demonstrating, through his courageous, flawed, deeply human characters, how individual people can restore the things that have been taken away. And if you’ve been worrying that you’ve lost your faith in the emotionally transformative power of fiction – Mr. Marra will restore that, too.” — Sarah Lyall, The New York Times

FROM THE FIRST CHAPTER: "THE LEOPARD: LENINGRAD, 1937"

In my generation the position of correction artist is a consolation prize for failed painters. I attended the Imperial Academy of Arts for a year, where I made small still lifes of fruit bowls and flower vases, each miniatureas realistic as a photograph, before moving on to portraiture, my calling, the most perfect art. The portrait artist must acknowledge human complexity with each brushstroke. The eyes, nose, and mouth that com- pose a sitter’s face, just like the suffering and joy that compose his soul, are similar to those of ten million others yet still singular to him. This acknowledgment is where art begins. It may also be where mercy begins. If criminals drew the faces of their victims before perpetrating their crimes and judges drew the faces of the guilty before sentencing them, then there would be no faces for executioners to draw.

“We have art in order not to die of the truth,” wrote Nietzsche in a quote I kept pinned to my workbench. Even as a student I knew we die of art as easily as of any instrument of coercion. Of course a handful of true visionaries treated Nietzsche’s words as edict rather than irony, but now they are dead or jailed, and their works are even less likely than mine to grace the walls of the Hermitage. After the Revolution, churches were looted, relics destroyed, priceless works sold abroad for industrial machinery; I joined in, unwillingly at first, destroying icons while I dreamed of creating portraits, even then both a maker and eraser of human faces.

Soon I was approached by the security organs and given a position. Those who can’t succeed, teach. Those who can’t teach, censor the successes of others. Still I could have turned out worse; I’m told the German chancellor is also a failed artist.

Most censoring, of course, is done by publishers. A little cropping, editing, adjusting of margins can rule out many undesirable elements. This has obvious limitations. Stalin’s pitted cheeks, for instance. To fix them you’d have to crop his entire head, a crime for which your own head would soon follow. For such sensitive work, I am brought in. During one bleak four- month stretch, I did nothing but airbrush his cheeks.

During my early days in the department, I wasn’t entrusted with such delicate assignments. For my first year, I combed the shelves of libraries with the most recently expanded edition of Summary List of Books Excluded from Libraries and the Book Trade Network, searching for images of newly disgraced officials. This should be a librarian’s job, of course, but you can’t trust people who read that much.

I found offending images in books, old newspapers, pamphlets, in paintings or as loose photographs, sitting in portrait or standing in crowds. Most could be ripped out, but some censored images needed to remain as a cautionary tale. For these, obliteration by India ink was the answer. A gentle tip of the jar, a few squeezes of the eyedropper, and the disgraced face drowned beneath a glinting black pool.

Only once did I witness the true power of my work. In the reading room of the Leningrad State University library, which I often visited to pore over folios of pre-Revolutionary prints, I saw a young man in a pea jacket search a volume of bound magazines. He flipped halfway through the August 1926 issue to a group portrait of military cadets. The cadets stood in three stern rows, ninety-three faces in total, sixty-two of which I had, one by one, over two years, obliterated.

I still don’t know which among the sixty-two he had been searching for, or if his was among those thirty-one still unblackened faces. His shoulders slumped forward. His hand gripped the table for support. Something broke behind his wide brown eyes. A gasp escaped his lips before he choked the cry with his fist.

With a few ink droplets I had inflicted upon his soul a violence beyond anything my most loving portraits could have ever achieved. For art to be the chisel that breaks the marble inside us, the artist must first become the hammer.