Excerpt:

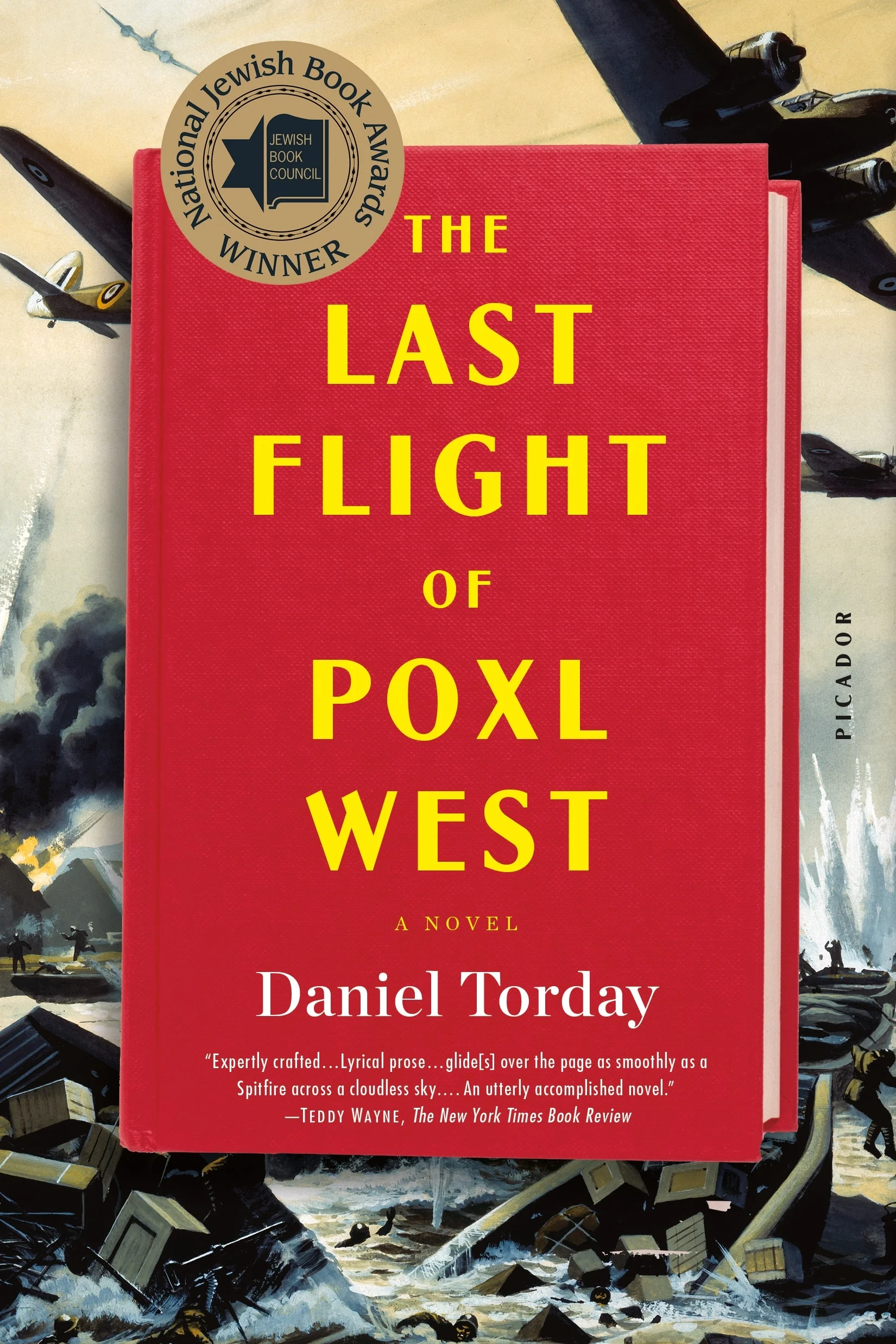

The Last Flight of Poxl West

by Daniel Torday

(From The Last Flight of Poxl West by Daniel Torday, on sale now from Picador. Copyright © 2016 by the author and reprinted by permission of Picador.)

A stunning debut novel from award-winning author Daniel Torday, in which a young man recounts his idolization of his Uncle Poxl, a Jewish, former RAF pilot, exploring memory, fame, and storytelling.

Poxl West fled the Nazis’ onslaught in Czechoslovakia. He escaped their clutches again in Holland. He pulled Londoners from the Blitz’s rubble. He wooed intoxicating, unconventional beauties. He rained fire on Germany from his RAF bomber.

Poxl West is the epitome of manhood and something of an idol to his teenage nephew, Eli Goldstein, who reveres him as a brave, singular, Jewish war hero. Poxl fills Eli’s head with electric accounts of his derring-do, adventures, and romances, as he collects the best episodes from his storied life into a memoir.

He publishes that memoir, Skylock, to great acclaim, and its success takes him on the road, and out of Eli’s life. With his uncle gone, Eli throws himself into reading his opus and becomes fixated on all things Poxl.

But as he delves deeper into Poxl’s history, Eli begins to see that the life of the fearless superman he’s adored has been much darker than Poxl let on, and filled with unimaginable loss from which he may have not recovered. As the truth about Poxl emerges, it forces Eli to face irreconcilable facts about the war he’s romanticized and the vision of the man he’s held so dear.

Daniel Torday’s debut novel, The Last Flight of Poxl West beautifully weaves together the two unforgettable voices of Eli Goldstein and Poxl West, exploring what it really means to be a hero, and to be a family, in the long shadow of war.

Before halftime on Super Bowl Sunday, January 1986, my uncle Poxl came over. He was just months from reaching the height of his fame, and unaware the game was being played. He wasn’t technically my uncle, either. He was an old friend of the family. For years he had taught at a prep school in Cambridge, where my grandfather had served as a dean. After a massive heart attack a year after I was born left my grandfather as much a memory to me as thin morning fog, Uncle Poxl came to fill the void. That Sunday he sat down in the living room and, speaking over the game’s play-by-play, started a story he could barely clap his gloves free of snow fast enough to tell.

A miracle had occurred that afternoon. His neighbor had died a few months back, and though my Uncle Poxl was consumed with the details of the upcoming publication of his first book, he’d advised the neighbor’s sons on the handling of the estate. The neighbor was an obscure literary novelist who’d enjoyed acclaim early and then none. Their father had left nothing more than his immense library—and thousands of dollars of debt from a mortgage on a house too far in arrears to sell. Uncle Poxl had become immoderately involved in figuring a way to help them, though it wasn’t clear what expertise they felt he could lend—decades ago he’d quit a job at British Airways to take a Ph.D. in English literature, then later dropped his dissertation on Elizabethan drama to finish what would in time become the successful memoir of his time flying Lancaster bombers for the RAF. Maybe they assumed that because he had owned a number of houses and apartments, he had a certain familiarity with ownership. Maybe people just assumed from listening to his confident tone that my uncle Poxl knew what he was talking about.

He was falling behind in grading for his classes, and in the early spring he would hit the road for his book tour, but something hadn’t let him give up this neighbor’s case.

“Then today,” Uncle Poxl said as Steve Grogan missed a receiver with a pass, “the deus ex machina!”

I had no idea what he meant at the time—I was barely fifteen, and what mattered back then were the Patriots and the Red Sox, a girl named Rachel Rothstein I was after in my Hebrew class who couldn’t have cared less for some wizened British war hero. But that Sunday I was too drawn in by his unerring voice, its dry gravity and utter self-belief, not to find out what happened to his neighbor’s sons. Somehow his voice had found the only register that could drown out the game’s clamorous announcers.

“Willie, the younger son, asked me if I’d help pack,” Uncle Poxl said. “He figured he’d give the books away.”

Poxl had noted my eyes on him now, not just my parents’. The volume of his wry voice rose perceptibly.

“We were a dozen books in when I dropped Saul Bellow’s Herzog. I picked it up, and a crisp hundred fluttered to the ground. Willie and I looked at it like it was—well, like it was a rabbi on a football field.”

He looked at me. The Bears scored. I missed the play and the replay. “Julian had used hundred-dollar bills as bookmarks in every one of his books. He’d get paid two hundred dollars a review, and put half back into the books. They hadn’t counted it all yet, but there must have been near to a hundred thousand dollars in those books—he didn’t write a review every week, but he wrote for that paper regularly, and others. Maybe he thought his sons would find it all. Willie doubted it, and I did, too—we were a pile of cardboard boxes away from handing his estate to the Harvard Coop!”

Uncle Poxl kept talking, hauled along by the wonder of the thing. I’d rarely seen him so animated. This was the first time we’d spent alone with him since he’d finalized copyedits on his memoir, and his appearance at our house was a surprise, given the frigid air and snow outside. We’d assumed we wouldn’t see him again until his first reading, here in Boston, scheduled for the week after the book’s publication date. I’d been longing to see him, my eccentric European uncle who’d lived so much life. But now the Patriots were in the Super Bowl for the first time, and my tongue buzzed like it did after I woke from a nap. My mother changed the subject, and by then I’d stopped caring about the game. Would the contents of a book ever carry the same meaning again?

This image of hundred-dollar bills spilling out of the pages of books would plague me for years. I tried to watch the end of the football game, but Grogan was awful, and a three-hundred-pound Bears lineman known as “the Refrigerator” scored a touchdown, and I couldn’t set my mind to anything but my uncle Poxl and when I’d finally get to read his stories between bound pages.